Today’s morning report case involved a woman with a previous

history of metastatic malignancy presenting with dyspnea. She was found on imaging to have a

substantial pleural effusion as well as a substantial pericardial

effusion. We spoke about a number of

valuable learning topics:

· Whenever you are confronted with someone with a

pericardial effusion or even a patient with a condition that would predispose

to effusions, you should consider

pericardial tamponade as a diagnostic entity. Without considering it, you won’t test for it

or diagnose it!

· Conditions that predispose to effusions are:

o

Pericarditis

can produce serous or blood effusions, especially for anticoagulated patients

o

Infections

such as tuberculosis

o

Malignancies

like lung cancer, lymphoma, or any metastatic disease

o

Uremia

producing uremic pericarditis and an effusion

o

Post-myocardial

infarction pericarditis leading to an effusion

o

Conditions

leading to arterial bleeding within the pericardial sac (dissections,

iatrogenic injury, etc.)

· It is important to note that the pericardium is

a rigid structure that can become compliant with time. Therefore, malignant effusions that have as

much as 1.5L of fluid may not produce pericardial tamponade if they develop

slowly. By contrast, 30cc of arterial

blood from a coronary artery dissection immediately into a rigid pericardium

can rapidly produce tamponade.

· There are several features to find on physical

examination when we discuss pericardial tamponade:

o

From a

vital sign perspective, patients are often hypotensive. This has to do with impairment of atrial info

to both sides of the heart owing to increased pericardial pressure.

o

It is

valuable to perform a pulsus paradoxous

in this and other conditions. The pulsus

paradoxus is inaptly named because it is actually an exaggeration of a normal

phenomenon. To measure it, take a blood

pressure with auscultation – when deflating the cuff slowly, you will hear

Korotkoff sounds only on expiration beginning at a certain pressure. Note this pressure and continue – you will

then hear the sounds throughout the respiratory cycle. The difference between those two pressures is

the pulsus paradoxus. Many have

suggested that this phenomenon occurs due to reduced pulmonary vascular

resistance upon inspiration, increased venous inflow into the RA/RV, and then

septal bowing into the LV impairing LV outflow.

While this makes sense, it is not seen echocardiographically even during

tamponade. Instead, the mechanism is

thought to be related to the gradient of pressure in the pulmonary veins

(mostly affected by the intrathoracic pressure) and the left atrium (mostly

affected by pericardial pressure).

Normally, when you breathe in, your intrathoracic pressure becomes

negative meaning that there is a slight impediment to flow from pulmonary veins

to left atrium. That impediment (and the

pulsus paradoxus) becomes larger if the negative pressure in the thorax

increases (e.g. during an asthma exacerbation, COPD exacerbation, or pulmonary

embolism) or if there is an impediment to left atrial inflow (high

intrapericardial pressure). Pulsus

paradoxus does not occur (at least to

the same level) with constrictive

pericarditis because the issue there is not pressure being transmitted onto the atrium, but rather rigid pericardium that resists

stretching as soon as the heart fills.

o

Frequently

overlooked but useful according to the JAMA rational clinical exam, is

tachycardia.

o

When

examining the patient’s neck, you will often notice distended neck veins, once

again owing to obstruction of venous inflow.

o

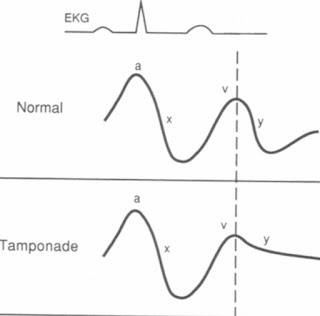

The JVP

waveform (easier to view on a central venous catheter than by eye) will usually

show a blunted y-descent which can

help distinguish tamponade from other pericardial problems. The y-descent occurs when the tricuspid valve

opens and passive filling of the ventricles begins – high pericardial pressures

inhibit right atrial and right ventricular inflow. The x-descent is still prominent in tamponade

because there is a vacuum phenomenon that occurs during ventricular systole

allowing blood to enter despite the high pericardial pressures.

o

One often

hears muffled heart sounds, but this isn’t as common as you may think.

o

On ECG,

the common findings are low voltages (usually if there is a lot of pericardial

fluid) and electrical alternans

meaning that the QRS axis changes from beat-to-beat. You can think of the heart “swinging” in the

pericardial sac.

· To treat tamponade, which is a mechanical

problem, usually a mechanical solution is required. Pericardiocentesis can be performed

percutaneously, but surgical options such as a pericardial window are also

possible. The medical management of

tamponade in the interim usually involves provision of a lot of intravenous

fluids.

· Tamponade needs to be distinguished from two

other syndromes – Constrictive

Pericarditis and Restrictive

Cardiomyopathy.

|

|

Tamponade

|

Constrictive

Pericarditis

|

Restrictive

Cardiomyopathy

|

|

Vitals

|

+++ Pulsus

paradoxus, hypotension

|

Smaller pulsus,

hypotension

|

Hypotension

|

|

JVP

|

Elevated

|

Kussmaul sign (rise

with inspiration)

|

Kussmaul sign

|

|

Apex Beat

|

Impalpable

|

Impalpable or retracting on systole

|

Palpable

|

|

Heart sounds

|

Muffled

|

Pericardial knock

|

S3 but no knock

|

|

Ventricular

Interdependence (on angiography)

|

High

|

High

|

None (e.g.

concordant respiratory changes on simultaneous RV/LV recording)

|

· It’s worth noting that there are situations

where the pulsus paradoxus is absent

despite the patient having tamponade.

The main one is a large atrial septal defect, which allows equalization

of the atrial pressures and obliterates the pulsus.

Further Reading:

Little, W. C., &

Freeman, G. L. (2006). Pericardial disease. Circulation, 113(12),

1622-1632.

Roy, C. L., Minor, M.

A., Brookhart, M. A., & Choudhry, N. K. (2007). Does this patient with a

pericardial effusion have cardiac tamponade?. JAMA, 297(16),

1810-1818.